The professor • legacy

Getting to the Point is the Hideaway Point blog. It is the place where we share our larger vision for this special place - what inspires us, what we value and the hopes and dreams we have for Hideaway Point.

The professor was written on 9 February 2024 for the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society - shared with permission from author Matthew Dacso MD, MSc, FACP • Department of Global Health & Emerging Diseases, UTMB School of Public & Population Health, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Texas, USA Correspondence Email: mmdacso@utmb.edu (photo and article below)

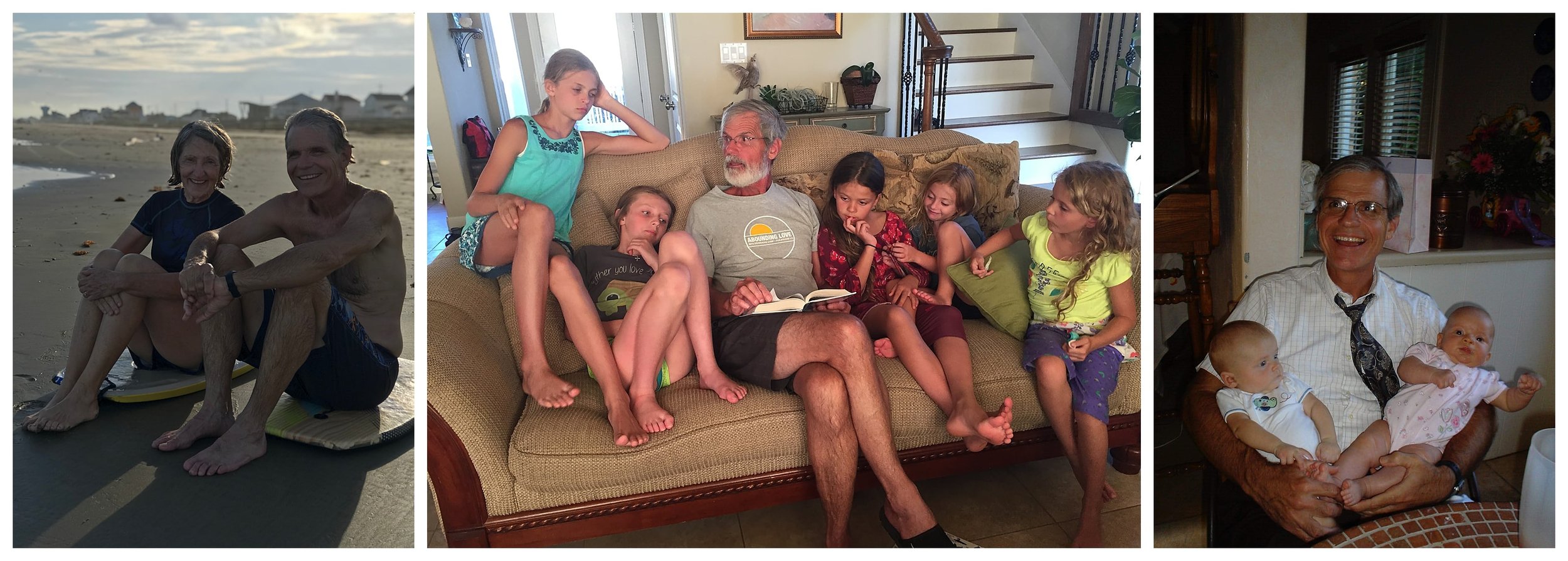

Dr. Dacso was in Ben’s medical school class at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston Texas. In 2005 when we moved to Delaware for Ben’s training, Matthew stayed on as a resident in Galveston. In 2008 Ben’s father (Dr. Richard Goodgame - the professor) became the UTMB internal medicine residency program director. Matthew was first Rick’s student, then his colleague & friend and now his personal physician.

This beautifully written story is about Matt’s relationship with Rick (who now has Alzheimer’s disease). It is also about two people that I admire more than words can express - Susan and Rick Goodgame. I’ve taken the liberty of adding photos between the words that Matthew wrote. I hope that it will add relevant context about the professor - a faithful and consistent force in this world. We are thankful for him in a million different ways.

The Professor greets me in the driveway. It's a tall brick house, the same I have visited several times. We embrace. My arms slip around his frame. He seems thinner. “Have you been here before?” He asks with a smile. “Sure have, the place looks great,” I respond, smiling back.

We go inside. The place is clean, free of clutter, unlike my own home. I am envious, but then realize that maybe this is to keep things straightforward so as not to upset or confuse him. He is 74 now and no longer uses a phone or responds to text messages. It is stressful for him to operate the device, which is filled with so many words, so many people, and so many unidentifiable images and names that he should remember but cannot. The phone is also a reminder of what he now cannot do. It is probably much better for him to live without it.

We enter the breakfast area where his wife joins us. There is coffee, toast, oatmeal, and cereal. “May I bless this meal?” He asks. “I would love that,” I respond. He thanks the Lord for the food, for my visit, for my family, and for guiding me on my journey. “In Jesus' name, amen.”

•

I serve myself some coffee and toast. He has Raisin Bran. I sat at this table about 6 months ago when I came for lunch. I should have brought something but instead, I just seem to come every time empty-handed and eat their food. With kind eyes, they reassure me that it's ok. The three of us sit down and start chatting between bites. I ask him how he is doing. He pauses and looks at his wife. “How am I doing?” “You can answer that one,” she responds patiently. “Then I think I'm ok,” he says with a half smile.

He is a little more withdrawn this time. He says less. He relies on his wife for most answers. But he is well overall. They take walks every day. He does the yard because it brings him peace. They have family close by. They go to church and see church friends socially. He still reads, though less than he used to. He has over 20 grandchildren. “There are definitely people and lots of children around,” he says, indicating to me that he doesn't always remember who the people are around him, but that he knows that they bring him happiness.

I look at the Professor and reflect on what an incredible human being he is. He did his medical training at Johns Hopkins and Massachusetts General Hospital, then practiced academic gastroenterology for many years, teaching countless residents and fellows along the way. He arrived at our institution to be the internal medicine residency program director at just before our region was battered by Hurricane Ike in 2008. He could have left at that moment, but instead, he put the program on his back and helped lead it out of crisis. It became an outstanding training program, largely because of the dedication and commitment he had to the housestaff. A true Oslerian, he was known for his engaging and enlightening bedside rounds. I remember many residents remarking that their pathway to a successful fellowship match was paved by the Professor's comprehensive, detailed, and thoughtful letters of recommendation. He retired in 2018 when he started to notice issues with his memory.

There were so many stories I got to hear from the Professor over the years. He had lived in Uganda from 1980 to 1989, right after the civil war and at the very beginning of the HIV epidemic. He saw so much during those tough times for that nation. When we went there together, every place we visited treated him like a celebrity coming home. He was clearly loved by so many people, and for good reason. As a missionary physician, he had a truly immersive experience. His wife, born to a family of missionaries, was raised in east Africa and became his true life partner. Their fifth (and final) child was delivered at Mulago Hospital, the largest public hospital in Kampala. He learned Luganda. He did so much during his time there. He told me about his experience being part of the response to a typhoid fever epidemic. He told me about the “citizenship training” program that he (along with all Ugandans) had to participate in to learn what it meant to be a citizen of a newly united country. He told me about getting called into the President's office and taken to task when people were starting to die from an unknown condition that they were calling “Slim disease.” The President apparently once said to him and his colleagues, “As physicians, you must figure out how to treat this disease and inform me on what to do about it.”

At some point, I have a memory about the time we went to Uganda together. I tell him about it. I recount it most times I come here because it is one of my fondest memories of us together. It was 2012, during the rainy season. We were in a van with a driver going back to Kampala from the southwest part of the country, where we were visiting some partner hospitals. On the way, we had two tire blowouts, which exhausted our spares. Our driver pulled to the side of the road, took one of the spares and hailed a “boda boda” (motorcycle taxi) to get the tire repaired in town, about 20 min up the road. The Professor and I sat by the van on the side of the highway for about 2 h, just watching the village life unfold around us, children running around, people carting around large bushels of matoke (large plantains that mash into the substrate for any Ugandan meal), cars, motorcycles, and people all jockeying for space on the road. The professor and I were sitting on the front hood of the car chatting when we saw our driver's familiar face emerge from over the hill. He was sitting on the back of a motorcycle, beaming proudly, carrying a repaired spare tire, which meant that we could now continue on our journey. As I told that story, we laughed. “I seem to remember some- thing like that,” he remarked with a grin.

Where are those memories? Does he remember the patients he treated, the doctors he mentored, the seminal papers he wrote, the lives that he undoubtedly had a hand in saving? Does he remember his interactions with the President of Uganda, or our spare tire story from that country's back roads? Are they all in there, locked away somewhere, inaccessible?

•

We finish our breakfast. There is a lull in the conversation. “Should we pray for Matt?” his wife asks. “That sounds great,” he responds. We bow our heads and pray. I don't usually pray. But when I am with him it brings me peace. I know that it is one of the forms of communicating lovingkindness that he is most comfortable with. It brings him peace as well.

His wife is holding his hand. Her head is bowed, eyes closed. Her eyes are watering. Maybe it's from the meal, or maybe it's the weight of the moment. This can't be easy for her, I think. I imagine those eyes watering frequently, as mine also swell. He goes first. His voice is soft. He works hard to keep the ideas together. “Matt, we thank you for being here. We appreciate the good things you do. Tough times. And the good stuff.” The sentence fragments continue. They are like puzzle pieces, jumbled but all fitting together and making sense somehow. “In Jesus' name, amen.”

•

It's his wife's turn. I know that she is paraphrasing, communicating what the Professor cannot. “Matt, we are grateful for you. We love you. We pray for you and your family. We pray for peace in the world. In Jesus' name, amen.”

We take our plates to the sink, our hearts and stomachs full. I hug him and his wife. As we walk to the door, I reflect. For me, he will always be the Professor I know him to be. She will always be a rock, caring for him as a true soulmate would. Even though his disease has taken his memories, they live on in me, in his family, in all those around the world whose lives he has touched and for whom his name immediately brings a smile (and usually a story of something great that he did for them). We carry those memories for him now, and they are the greatest blessing we could ever hope to have.

He sees me off in the driveway. It's a tall brick house, the same I have visited several times. We embrace. My arms slip around his frame. He seems thinner. “Have you been here before?” He asks with a smile. “Sure have, the place looks great,” I respond, smiling back.

•

I will be back.

We believe in the power of retreat and would love to help you imagine what time away at Hideaway Point could look like for you and your family, community, organization or business. Let us know how we can help.